What are the best ways to stop parental alienation? In today’s blog Peter Graburn, senior family lawyer at MacLean Law explains what parental alienation is and the ways to stop this heartbreaking pattern of abuse. Call us toll free across Canada at 1 877 602 9900

Best Ways To Stop Parental Alienation 1 877 602 9900

Parental Alienation (together with domestic violence) is one of the most difficult and serious situations in family law. It can often lead to long-term damage to the personal growth, mental health and future relationships of children. It is abusive to children. It is toxic. In a previous article, Toronto Parental Alienation Lawyers, we discussed the progression of how Ontario Courts have addressed Parental Alienation (once it has been professionally identified), from in effect saying ‘there’s nothing we can do about it’, to taking drastic action to attempt to ‘reverse’ the negative effects of the alienation on children. In this article we review the most recent Ontario cases when the Courts have found significant Parental Alienation (“PAS”) to exist. These cases provide guidance to Canadians on the Best Ways To Stop Parental Alienation.

What is Parental Alienation? 1 877 602 9900

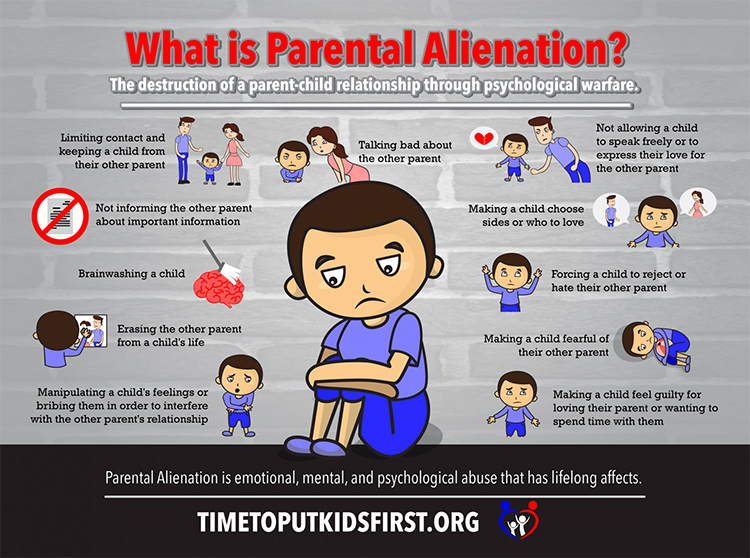

Before we talk about the Best Ways To Stop Parental Alienation, we need to know what parental alienation is. Recent conferences on the topic occurred at UBC.

Parental Alienation Syndrome (PAS) is when a parent intentionally and systematically attempts (often during high conflict child custody disputes) to negatively influence the child’s relationship with the other parent, often leading to the complete breakdown of that relationship. It is often perpetrated by parents with a personality disorder [Narcissistic Personality Disorder (NPD), Bi-Polar, etc.]. It needs to be distinguished from the natural estrangement of a child from one (or both) of their parents. Some indicators of Parental Alienation in a child include:

- becoming increasingly argumentative, challenging and defiant with the alienated parent;

- becomes increasingly critical of the alienated parent (often repeating the alienating parent’s criticisms), and;

- demonstrates an expectation / entitlement to receive things from the alienated parent.

And in the Alienating Parent:

- speaking negatively about the other parent;

- influencing and coaching the child about Court matters, and;

- withholding the child from the other parent.

Here is a great article on what PAS is and the Best Ways To Stop Parental Alienation.

Reversing Parenting 1 877 602 9900

Courts now seem more in tune with the spectre that parental alienation may exist in certain high conflict child parenting disputes. Courts are seeking new ways to deal with the issue. So: What are the best ways to stop parental alienation?

The Courts are becoming increasingly aware (and concerned) of the prevalence of Parental Alienation in Canadian family law cases. Studies (ie. Bala et al., Canadian Research Institute for Law and Family) have shown that Parental Alienation was found to have occurred in between 22-35% of the cases where it was alleged. So how have the Ontario Courts responded to (and tried to reverse the on-going negative effects of) the rise of Parental Alienation when it is alleged? Three (3) recent Ontario cases highlight this shift.

In 2018 [see: AM v. CH (2018 ONSC 6472); upheld on appeal (2019 ONCA 764; 2019 ONCA 939)], in “a sad case about a mother successfully alienating three children from their father” (at para. 1), Justice P. Nicholson removed a 14-year old child (against his wishes) from any contact with the alienating Mother or his other siblings (for 6 months) and placed him in the sole care and decision-making of the alienated Father (together with reconciliation therapy), noting (at para. 110):

“Once a finding of alienation is made, courts must then determine the appropriate order. MacPherson J. in C.(W.) summarized the available orders, as articulated by Dr. Fidler, as the following:

1) Do nothing and leave the child with the alienating parent;

2) Do a custody reversal by placing the child with the rejected parent;

3) Leave the child with the favoured parent and provide therapy; or

4) Provide a transitional placement where the child is placed with a neutral party and therapy is provided so that eventually the child can be placed with the rejected parent.”

In August 2021 [see: Misiuda v. Misiuda (2021 ONSC 5258)], in a case described as the “highlight reel of how not to behave as a parent” (para. 85), Justice R.F. MacLeod, in giving limited parenting time to a Father who had intentionally and systematically attempted to affect the children’s relationship with their Mother, stated (at various paragraphs):

“When he did not get his way, he promised to ruin her by weaponizing all three children against her. The last six years of family conflict and litigation have been the result of John fulfilling his promise… (para. 16). In hindsight, this was not a threat. This was John laying out the blueprint of his path to victory. Six years later, his plan has been executed. No one is victorious, certainly not the children (para. 50). John acted as if his children were pawns to be used to achieve his goals… When it comes to determining parenting responsibility, John’s behaviour is disqualifying (para. 86). It is clear that his children have been damaged as a result of his conduct, despite the fact that the two eldest now live primarily with him (para. 127)”.

Most recently, in September 2021 [see: WS v. PIA (2021 ONSC 5976); upheld on appeal (2021 ONCA 923)], Justice McGee transferred primary care and decision-making over the parent’s young children to the Father with the Mother having no contact (except for Zoom calls) for 90 days, noting the Mother’s “two parallel and competing narratives” (para. 8) of encouraging, while at the same time intentionally undermining, her children’s relationship with their father (including causing the 6-year to make allegations of the Father sexually abusing his 4-year old brother). In noting the four (4) options for parenting (and approved “cooling off” period with the Alienating Parent, together with reconciliation therapy) set out in AM v. CH (above) once Parental Alienation is identified, Justice McGee concluded (at para. 33):

“In my view, a reversal of primary care is the most difficult of parenting decisions. It is an option that must be approached with caution, and each case must be considered on its own facts. A reversal is not a vindication of which parent is right or wrong (original emphasis). It is a finding as to which parent can best provide physical, emotional, and psychological safety and security to a child in distress. Which parent will best protect the child from the conflict and place the child’s well-being above the litigation “win”.”

The Ontario Courts have come a long way in dealing directly with Parental Alienation since 1997 when they concluded that, given the alienated child’s age (13) and wishes, making a change in parenting was “unrealistic and unworkable” [see: DeSilva v. DeSilva, 1997 CarswellOnt 221 (OCJ, Gen. Div.) at para. 24].

Today (2022), Ontario Courts are much more willing to take direct and decisive action to try to prevent further damage to the alienated parent-child relationship and thus the child, including totally ‘reversing’ the parenting and decision-making arrangement even over the (often older) child’s wishes and (sometimes) verbal and physical protest (in AM v. CH, above, after the change in care, the child physically attacked and assaulted the Father). Importantly, the Courts are increasingly realizing this should only be done in conjunction with therapy and counselling involving both parties (if possible) and the child(ren).

Parental Alienation – it’s serious. It’s ‘weaponizing’ and damaging children. It’s toxic. It’s abuse.

IF you have questions on the Best Ways To Stop Parental Alienation, contact our child parenting dispute lawyers at any of our offices across Canada. Toll free 1 877 602 9900.