Our top-rated Vancouver Paternity Test Lawyers know that DNA paternity tests also called DNA parentage testing applications have become a television spectacle thanks to shows hosted by the likes of Maury and Jerry Springer. In family court, applications concerning paternity tests are frequently brought forward, and judges can make an order that a party takes a paternity test. Vancouver paternity test lawyers handle cases in the BC Supreme and BC Family Provincial Court involving proof of parentage when child parenting time, guardianship and child support issues are involved. In today’s blog Fraser MacLean one of our experienced Vancouver Paternity Test Lawyers explains how paternity testing also called parentage testing works.

Vancouver Paternity Test Lawyers know paternity tests can help confirm whether the person you think is your child’s biological parent is, in fact, the parent. If a paternity test reveals that a man is a biological father, he may be a guardian of the child with parental responsibilities and parenting time with the child. The father of the child, just as the mother, will also have a legal obligation to support the child financially.

Vancouver Paternity Test Lawyers 1 877 602 9900

Section 33 of the B.C Family Law Act (“FLA”) gives the court the authority to order a paternity test in all circumstances when parentage is at issue or when necessary to determine parentage for an order respecting child support. Both the Supreme Court and the Provincial Court can order a person to take a paternity test to find out for sure who the legal parents are.

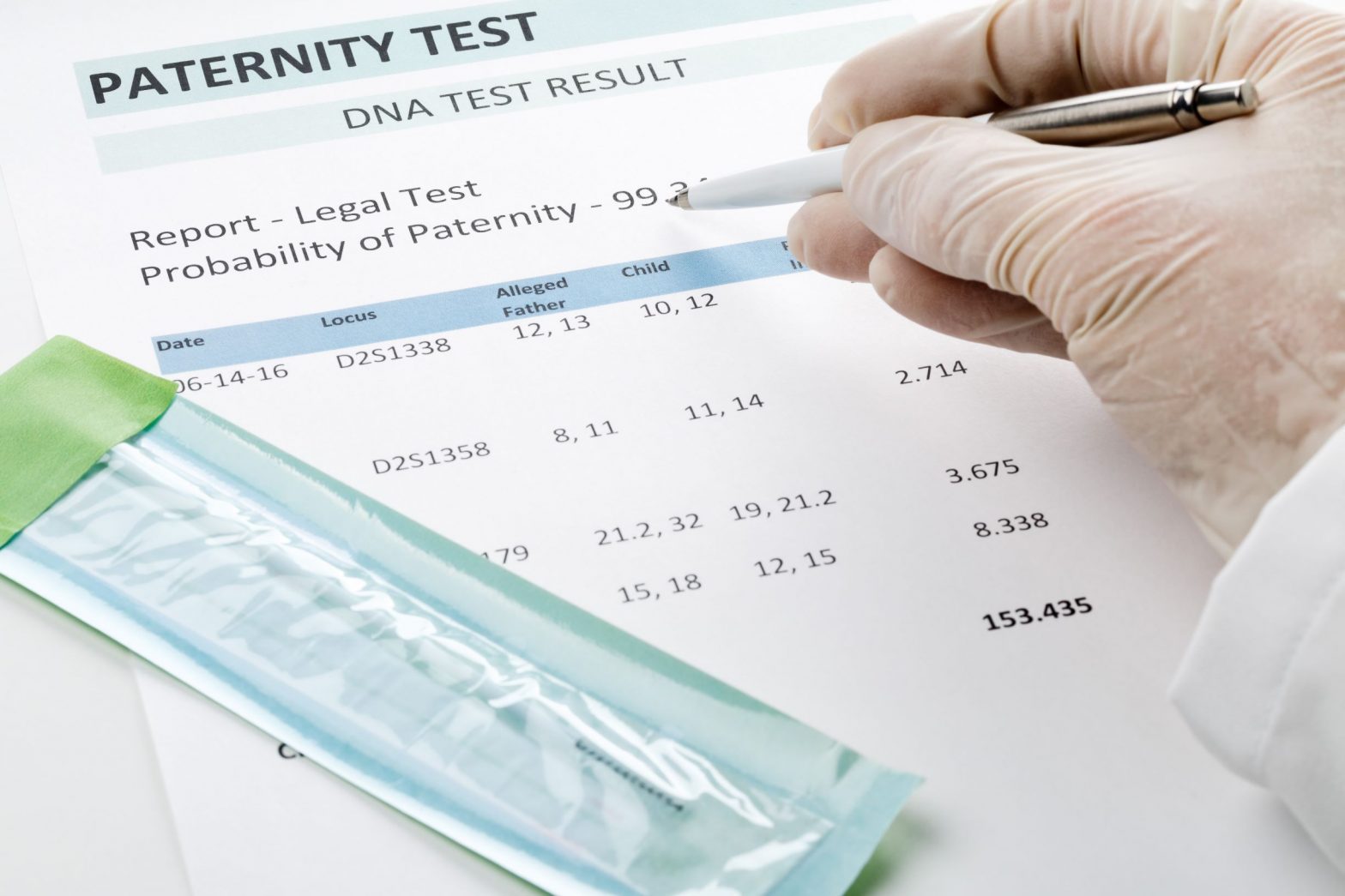

An application for a British Columbia paternity test is brought by a notice of application and affidavit. British Columbia Paternity tests are typically done by blood samples or cheek swabs. Our Vancouver Paternity Test Lawyers attach an article by the Mayo Clinic here, which provides a good overview of paternity/DNA testing.

If a person you suspect is your child’s biological father refuses to voluntarily take a paternity test, our Vancouver Paternity Test Lawyers recommend you hire an experienced family lawyer to help you bring on an application for a paternity test may be necessary.

The experienced DNA paternity test lawyers at MacLean Law represent both mothers and fathers through paternity testing disagreements and we can help establish appropriate child support and parenting arrangements through court order or written agreement.

DNA Parentage Testing Lawyers 1 877 602 9900

When is the onus on the man to prove he is not the child’s father?

Under the FLA, a man is presumed to be the child’s biological father if:

- He was married to the child’s birth mother on the day of the child’s birth;

- He was married to the child’s mother and, within 300 days before the child’s birth, the marriage was ended by his death or divorce;

- He married the child’s birth mother after the child’s birth and acknowledges that he is the father;

- He was living with the child’s birth mother in a marriage-like relationship within 300 days before, or on the day of, the child’s birth;

- He, along with the child’s birth mother, has acknowledged that he is the child’s father by having signed a statement under section 3 of the Vital Statistics Act;

- He has acknowledged that he is the child’s father by having signed an agreement under section 20 of the Child Paternity and Support Act;

If any of these have taken place and the man later denies or questions paternity, the onus will be on him to prove he is not the biological parent of the child with a paternity test.

Vancouver Paternity Test Lawyers 1 877 602 9900

The case R.J.P. v. N.L.W., 2013 BCCA 242 involved an appeal from a married couple (the “appellants”) from an order which granted a paternity test in favour of the respondent. The appellants were married in August 2003 and separated in April 2008. After separation, the appellant wife met the respondent and they had a sexual relationship that continued until December 2008. The appellants started to communicate again in September 2008 and resumed their sexual relationship which continued through December 2008. The appellant wife became pregnant in December 2008 and the appellants reconciled completely in July 2009. The child, H., was born in September 2009.

Shortly after H was born, the respondent filed a notice of family claim seeking orders for joint guardianship, joint custody and access to H, and a paternity test. The lower court accepted the respondent’s evidence that he had a sexual relationship with the appellant while she was separated from her husband and granted an order for DNA testing to determine the paternity of the child. In upholding the Supreme Court justice order allowing the respondent’s application for a paternity test, the Court of Appeal stated the following:

[17] Turning then to the main issue, as I see it: did the trial judge fail to consider whether allowing a paternity test to proceed at this stage would be contrary or detrimental to the interests of H? In particular, as I understand their argument, the appellants say that the respondent is a “stranger” who is trying to disrupt their family unit, and that proceeding with the paternity test will detrimentally affect their family and, in particular, H.

[18] In I.M. v. K.M., the plaintiff brought an application for an order pursuant to Rule 30, the predecessor to R. 9-5, that paternity tests be conducted to determine whether he was the biological father of A.M., then 18 years old. Madam Justice Neilson noted that the interests of justice will generally best be served by obtaining blood test evidence so that the truth may be ascertained (at para. 16). She rejected the respondents’ argument that there was an insufficient evidentiary basis upon which to find that the interests of justice required a determination of A.M.’s paternity, in part because the respondent mother’s affidavits did “not set out any clear statement that the plaintiff was the only person with whom she had sexual relations during the period surrounding A.M.’s conception” (at para. 21).

[19]In determining that it would not be contrary to the interests of justice to order a paternity test in the circumstances, Neilson J. stated (at paras. 23-24):

[23] As noted previously, the plaintiff seeks a declaration of his status as a parent. The result will clarify the legal rights and obligations he and A.M. have with respect to each other. Earlier decisions have found that the interests of justice, and the interests of a child involved in such a matter, are often best served by ascertaining the truth with respect to paternity. While one must guard against permitting blood tests of a child to be taken if it would be against the child’s interests, the court need not be satisfied that the outcome of the tests will necessarily benefit the child: J.S.D. v. W.L.V. at para. 23; Schuh v. Schulzer at para. 18.

[24] It is difficult to envisage what mischief or detriment may arise if the issue of A.M.’s paternity is determined. The authorities are clear that public policy no longer requires a child to be protected from the status of illegitimacy: J.S.D. v. W.L.V. at para. 23. She has no ongoing relationship with the plaintiff, and in fact shuns him. Even if the plaintiff is found not to be her father, she will remain a child of the marriage, and the plaintiff will remain obliged to continue to pay child support, which he has said he will willingly do.

[20] In my opinion, where an applicant has established that the issue of paternity is before the court, there is no principled reason why the court should treat an application for an order for a paternity test differently depending on whether the applicant is or has been a member of the family unit. While the presumption of legitimacy requires that a “stranger” meet the onus of rebutting the husband’s paternity, the development of the law makes it clear that the “stigma” of illegitimacy can no longer play a role in determining whether an applicant should be granted access to blood tests to help him meet this burden.

[21] This position is consistent with an Ontario Court of Justice case with similar circumstances to those at bar, applied by the trial judge in this case: D.H. v. D.W., [1992] O.J. No. 1737 (QL). In that case, the applicant claimed to be the biological father to a child born to a married woman. The mother contended that the applicant should not be granted an order for a blood test without first successfully rebutting the presumption of paternity. In dismissing this position, Madam Justice Charron stated (at para. 8):

While there must first be an issue as to parentage in a civil proceeding before leave to obtain blood tests can be granted, I am unable to agree with my brother judge in the case of F.G. that there can be no issue before the Court unless the applicant can first prove on a balance of probabilities that someone other than the presumed father is the father of the child. In many instances – such as this case – this would have the practical effect of requiring the applicant to meet the ultimate burden on the issue of parentage before leave to obtain evidence in support of his case could be obtained. If the legislator intended the courts to take such a restrictive approach, it could easily have so stated in s. 10.

[22] While I note that in Ontario there is a statutory scheme dealing with paternity tests, in my opinion the reasoning in D.H. v. D.W. is nonetheless instructive on the question of whether to order such a test in this province pursuant to R. 9–5 of the Supreme Court Family Rules.

[23] In J.S.B. v. W.L.V., Rowles J.A. summarized the state of the law in British Columbia with respect to an application under (then) s. 30(1) of the Rules of Court for an order for DNA testing (at para. 26):

In summary, while there is no specific legislation in this Province governing the obtaining of samples for DNA testing to determine biological paternity, it has been clear since Bauman v. Kovacs [(1986), 1986 CanLII 740 (BC CA), 10 B.C.L.R. (2d) 218 (C.A.)], supra, that an order may be made under R. 30(1) requiring a person to provide the necessary samples for such testing, where biological paternity must be determined in order to resolve a disputed claim. Such an order is discretionary and, in the absence of guiding legislation, the principles which are to be applied in the exercise of that discretion must be derived from the developing case law. Those principles include recognition that DNA profiling provides evidence of a highly reliable kind when determining biological parentage and that the interests of justice will generally best be served by obtaining such evidence so that the truth may be ascertained.

[24] Those principles apply to this case, and were properly applied by the trial judge in ordering the paternity test. He had before him the circumstances of the case, including that the appellants were denying the respondent access to H., they did not want the respondent to have any contact with H., and the respondent has been consistent in his efforts be a part of H.’s life. In light of these factors, the judge exercised his discretion to order a paternity test, stating (at paras. 81-83):

[81] [The respondent] may be a stranger in law to the child but not in the classic sense where husband and wife were together at conception in a marriage relationship, and certainly not for lack of trying on his part to find out if he is the natural father.

[82] This is an application for a paternity test by DNA analysis, and nothing more.

[83] If the paternity test demonstrates that [the respondent] is the father then issues of guardianship, custody, access and child support may come to the fore at that time.

[25] I am not persuaded that the trial judge erred in so concluding and I would not accede to this ground of appeal.

[26] It is worth noting that the Family Law Act, S.B.C. 2011, c. 25, effective March 18, 2013, provides statutory guidance on these issues: see ss. 26, 31, and 36, which deal with presumptions of parentage, an application for a declaration of parentage, and an order for “parentage tests”. As the order appealed from was made before the Act came into force, these provisions do not apply here.

[27] The appellants put forward several other grounds of appeal in their materials. I have reviewed their submissions and supporting documents, and I am satisfied that there is no merit to these remaining grounds.

Conclusion

[28] The appellants have failed to show that the trial judge made a material error, seriously misapprehend any evidence, or made an error in law. The trial judge considered the relevant jurisprudence and the evidence before him, and it was open to him to make the order that he did. I see no basis on which to interfere with his findings.

[29] It follows that I would dismiss the appeal.